Unshackling LGBTQI+ Members: The APA's Bold Decision To End Diagnostic Persecution

How Science and Activism Led the APA to Remove Homosexuality from Its List of Disorders

When the American Psychiatric Association (APA) made the groundbreaking decision in 1973 to remove homosexuality from its list of mental disorders in the DSM-II, it wasn't merely an administrative adjustment—it was a seismic shift that forever altered the course of LGBTQI+ rights in America and beyond.

Behind this monumental move lies a compelling story of scientific rigor, grassroots activism, and a long-overdue reckoning with societal prejudice.

The battle to de-pathologize homosexuality was a microcosm of the larger cultural war brewing in the United States, and its ripple effects are still being felt today.

The Origins of Pathologizing Homosexuality

For much of the 20th century, homosexuality was regarded by medical professionals and society as a deviation from the norm, often viewed as an immoral and pathological condition.

In 1952, the APA's first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I) categorized homosexuality as a “sociopathic personality disturbance.”

This classification reflected the deep-seated prejudices of the time, reinforcing harmful societal views that led to discrimination, criminalization, and attempts to "cure" homosexuality through often torturous methods like conversion therapy or electroshock treatments.

This view of homosexuality as deviant wasn’t just a medical stance but also a legal and social one.

Homosexual acts were criminalized in many U.S. states, and LGBTQI+ individuals faced brutal persecution, sometimes even from the medical community that was supposed to help them.

It was not until the 1960s that these views began to be seriously challenged by new research and the burgeoning LGBTQI+ rights movement.

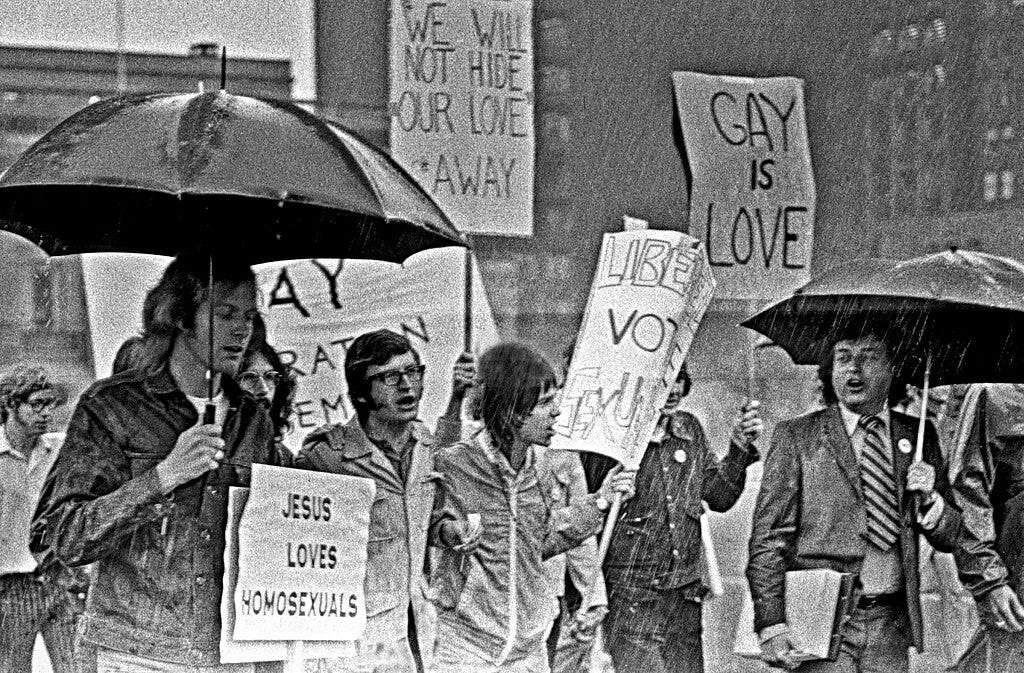

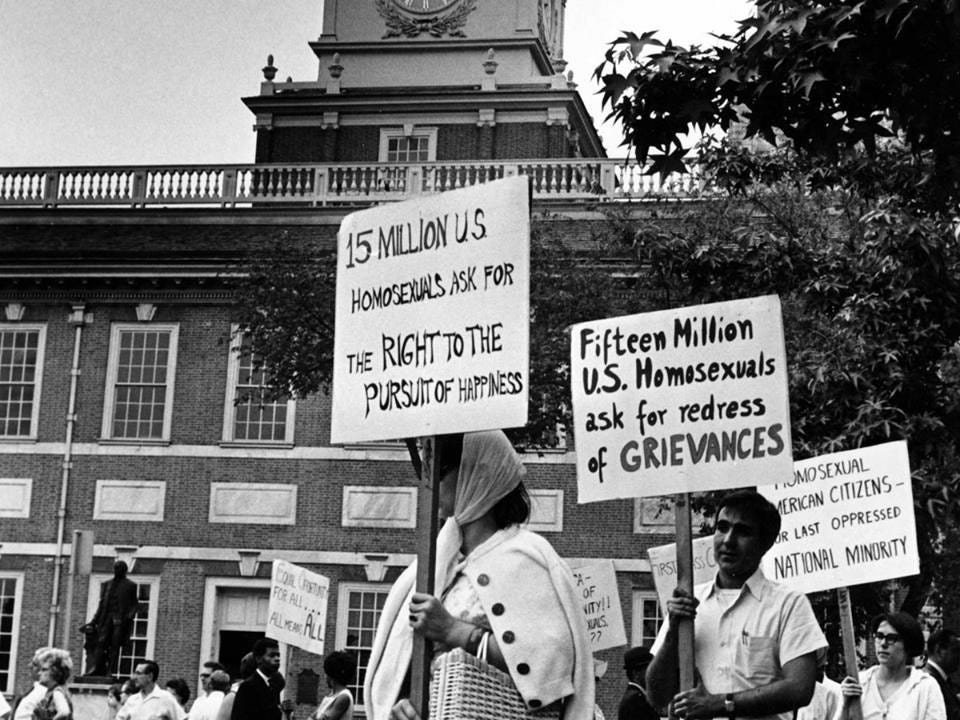

Activism Takes Center Stage

The late 1960s saw a surge of LGBTQI+ activism that culminated in events like the Stonewall Riots in 1969, which galvanized the movement for LGBTQI+ rights and brought new urgency to the fight against institutionalized discrimination, including that propagated by the medical establishment.

It was becoming increasingly clear to LGBTQI+ advocates that the classification of homosexuality as a mental illness by the APA was not only scientifically flawed but also fueled discriminatory policies and societal stigma.

One of the most influential activists in this fight was Frank Kameny, an astronomer turned LGBTQI+ rights advocate, who tirelessly campaigned against the classification of homosexuality as a disorder.

Kameny argued that no condition should be labeled a mental illness solely based on society's moral disapproval of the behavior. His fiery activism would eventually help spark one of the most significant changes in psychiatric history.

In 1970, during the APA’s annual meeting in San Francisco, LGBTQI+ activists, including Kameny, disrupted the proceedings and demanded the APA reconsider its stance.

This unprecedented confrontation forced the APA to directly address the mounting pressure from both activists and progressive psychiatrists who were calling for change.

One of the most notable moments of the meeting was when Dr. John Fryer, a gay psychiatrist, anonymously took the stage disguised as Dr. H. Anonymous, highlighting the personal toll that the classification took on LGBTQI+ psychiatrists and patients alike.

Fryer’s powerful testimony prompted the APA to examine its own role in perpetuating harm.

The Role of Science in Changing Minds

While activism played a crucial role in pressuring the APA, it was the accumulating scientific evidence that ultimately turned the tide.

Studies like those conducted by Alfred Kinsey in the 1950s and Evelyn Hooker in the 1960s were instrumental in debunking the myth that homosexuality was inherently linked to mental illness.

Hooker’s research, in particular, was groundbreaking. By comparing the psychological profiles of homosexual and heterosexual men, she found no significant differences in their mental health, effectively challenging the assumption that homosexuality was abnormal.

By the early 1970s, scientific consensus was shifting. The APA's leadership convened a task force led by Dr. Robert Spitzer to review the available literature on homosexuality.

The group’s conclusion was clear: homosexuality per se did not meet the criteria for a mental disorder. It was not inherently linked to distress, dysfunction, or disability.

This evidence-based approach was pivotal in convincing the APA’s Board of Trustees to vote in favor of removing homosexuality from the DSM-II in December 1973.

Controversy Within the APA

However, the decision was not without internal opposition. In the early 1970s, the APA was deeply divided, and there was considerable resistance from conservative psychiatrists who continued to view homosexuality as deviant behavior.

To quell this internal dissent, the APA leadership called for a referendum among its members. The vote resulted in a 58% majority in favor of the removal, effectively settling the issue within the organization.

Yet, even though homosexuality was no longer classified as a mental disorder, the APA introduced a new diagnosis—“sexual orientation disturbance”—which applied to individuals who were distressed by their homosexual feelings and sought treatment to change their sexual orientation.

While some saw this compromise as a way to placate conservative elements within the APA, it was still a step toward recognizing that the problem lay not with homosexuality itself but with societal and personal conflicts regarding sexual orientation.

This compromise diagnosis would later be removed in 1987 in the revised edition of the DSM-III-R.

Impact and Legacy: The Path Toward LGBTQI+ Liberation

The removal of homosexuality from the DSM marked a profound shift not only in psychiatry but also in how society viewed LGBTQI+ individuals.

It was an official recognition by the medical establishment that being LGBTQI+ was not a disorder that needed to be treated or cured but rather a natural expression of human diversity.

This decision also paved the way for further advancements in LGBTQI+ rights, from decriminalization to the eventual push for marriage equality and broader social acceptance.

However, the battle was far from over.

Conversion therapy, a practice aimed at changing an individual's sexual orientation, continued and still exists in some places today despite being widely discredited and condemned by the APA and other medical organizations.

The decision to remove homosexuality from the DSM helped to delegitimize these harmful practices, but their persistence shows that the path to full LGBTQI+ equality is still being paved.

In the years since, the APA has become a staunch ally of the LGBTQI+ community, advocating for the rights of individuals to live without discrimination or stigmatization based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.

The organization now openly condemns conversion therapy and supports the broader movement for LGBTQI+ rights, including the rights of transgender and non-binary individuals.

Conclusion: The Power of Science and Advocacy

The APA’s 1973 decision to de-pathologize homosexuality was a landmark moment in the history of LGBTQI+ liberation. It demonstrated the power of activism, science, and advocacy to challenge long-standing prejudices and create lasting change.

The road to equality is ongoing, but the removal of homosexuality from the DSM remains a pivotal turning point in that journey—a victory won by brave activists, forward-thinking scientists, and a community that refused to be silenced.

The APA’s decision wasn’t just about correcting a medical mistake—it was about changing the course of history.

The shift signaled to the world that the LGBTQI+ community deserved not just tolerance but respect and dignity, forever altering the landscape of human rights.

First B&W Image: Jearld Moldenhauer, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second B&W Image: First organized gay rights demonstration, Independence National Historical Park, 1965, public domain via picryl.